I Finally Understood Backpropagation: And you can too

Why the gradient is the direction of steepest ascent

- Let's begin with gradient descent

- Reviewing gradients

- Directional derivatives

- Finding the direction of steepest ascent

- Resources

The backpropagation algorithm is one of the key ingredients for the training of neural networks, but it's also probably the most difficult concept to grasp in understanding how things really work. At least in my own experience, it's been the one thing that I've struggled to gain a deep understanding of. After juggling between a plethora of materials on the subject, I got my own eureka moment and the pieces fell into place. Like me, you may also be self-taught through online courses and may have done a couple of projects but you still feel that twinge of half-knowledge, of only vaguely understanding what is actually going on when you are training neural networks (or any other machine learning model).

In this blog post, I would be letting you in on the intuition that I've developed, hoping that you would build on this to develop an even better understanding of this all-important concept. I also provide links to the resources that have been of great help to me.

But why?

Because that was the most glossed over bit for me. Many online courses would just tell you that gradient descent finds the partial derivative of the loss function with respect to the weights (ie. the gradient) and takes a step in the direction opposite to this gradient; Because the gradient points in the direction of steepest ascent, taking a step in the opposite direction would mean we move in the direction of steepest descent. But they never state why, I mean the why of the why. We take a step in the direction opposite to the gradient because it points in the direction of steepest ascent but the question (for me) really is: Why is the gradient the direction of steepest ascent?

The gradient is just a vector containing all the partial derivatives of a function. Hence the key idea here is really the concept of partial derivatives. Partial derivatives tell us how much a function would change when we keep all but one of its input variables constant and move a slight nudge in the direction of the one variable that is not fixed.

As an aside, typical neural networks contain thousands of parameters but for simplicity and ease of visualization, we would be considering functions with two variables: $f(x,y)$. Fortunately, everything we do here would generalize nicely to any number of dimensions.

For our two-variable case, the partial derivative tells us how much the output of the function would change if we keep the $y$ variable constant and move a slight nudge in the $x$ direction and vice versa.

Concretely

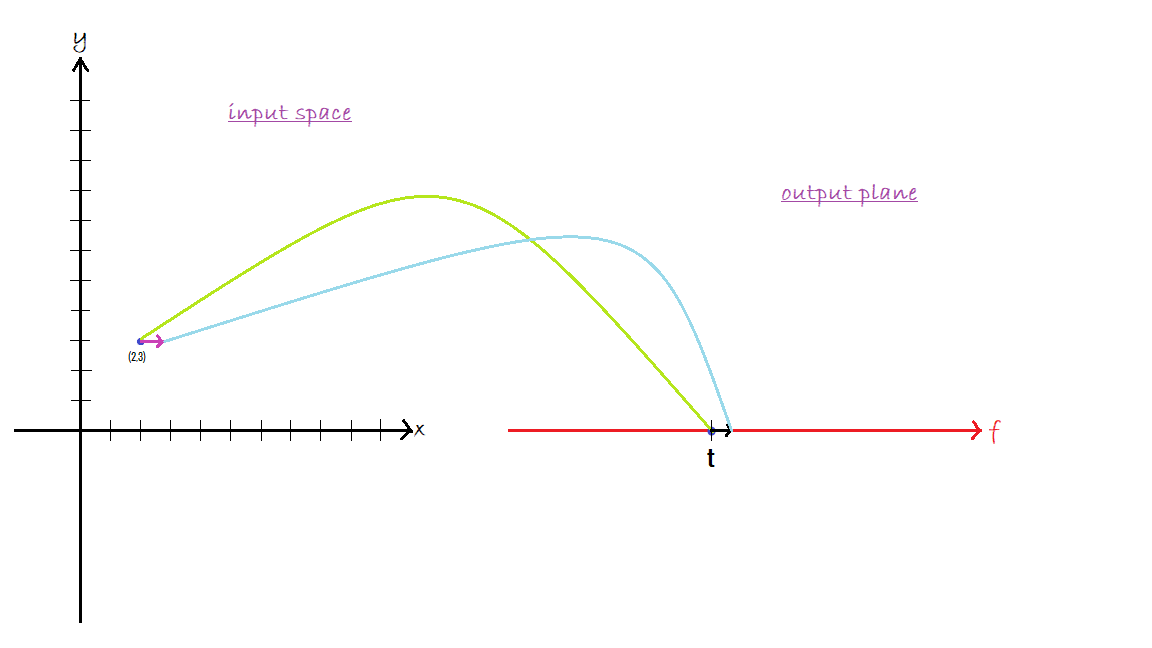

We are at the point (2, 3) in our input space which corresponds to a particular point t in the output plane, that is the output of our function is t for an input of (2, 3). The partial derivative with respect to $x$ tells us how much change would result in the output if we keep $y$ fixed at 3 and move slightly in the $x$ direction. Similarly, the partial derivative with respect to $y$ measures the resulting change in output when $x$ is fixed at 2 and we move a little nudge in the $y$ direction.

Let's consider the function: $f(x,y)=x^2y$. The partial derivative with respect to $x$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ is $2xy$, ie. we keep the $y$ as a constant and differentiate the whole term. Likewise, the partial derivative with respect to $x$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$ is $x^2$.

Remembering that the gradient packs together all the partial derivative into a vector, the gradient of this function would be: $$\nabla f=\begin{bmatrix} 2xy \\ x^2 \end{bmatrix}$$

At point (2, 3), the gradient would be $\nabla f=\begin{bmatrix} 12 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix}$. So a slight nudge purely in the x direction would cause a change by a factor of 12 in the output of the function while a similar change in the y direction would change the output of the function by a factor of 4.

Try deriving the partial derivatives for the function: $g(x,y)=3xy^3$

Hopefully, it shouldn't be difficult to see that the gradient of this function would be: $$\nabla g=\begin{bmatrix} 3y^3 \\ 9xy^2 \end{bmatrix}$$

The problem with partial derivatives is that they only tell us how things would change if we move in only one direction. Partial derivatives are partial because neither of them tells us the full story of how our function $f(x,y)$ changes when it's inputs changes. However, we do not only want to know how things change when we move in either the $x$ or $y$ direction, but we also want to know how much things would change if we move in any arbitrary direction within the input space. That's exactly what directional derivatives are for.

The directional derivative in a direction say $\vec{w}$ tells us how much the output of the function would change if we move a slight nudge in the direction of the vector $\vec{w}$. The directional derivative is found by taking the dot product of the gradient of the function and $\vec{w}$ ie. the direction in which we want to move.

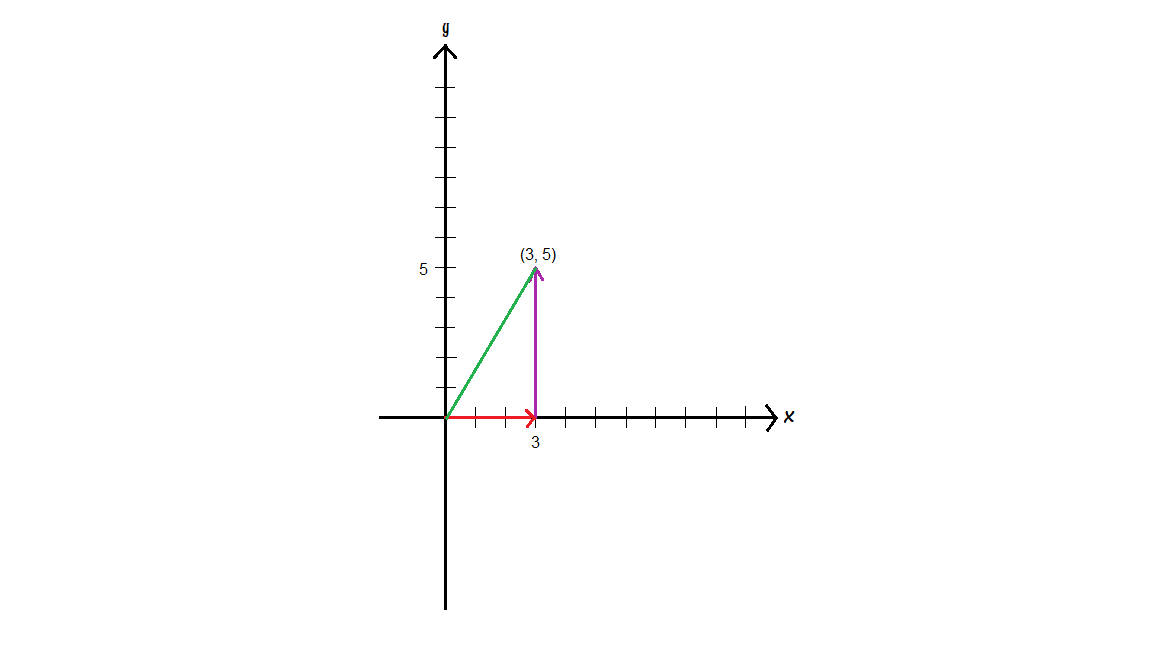

If $\vec{w}=\begin{bmatrix} 3 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix}$, then the directional derivative: $$\nabla_\vec{w}f = \begin{bmatrix} 2xy \\ x^2 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 3 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix} = 6xy + 5x^2$$

Evaluating the directional derivative at the point (2,3):

$$\nabla_\vec{w}f = 36 + 20 = 56$$

What this means is that given that we are at the point (2, 3) in our input plane, taking a tiny step in the direction of the vector (3, 5) would change the output of our function by a factor of 56.

Another way to look at this is to consider that in our input plane (ie. the x,y plane), any point or direction in this plane can be thought of as a combination of movements in the $x$ and $y$ directions.

In the image above, $\vec{w}=\begin{bmatrix} 3 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix}$ is a combination of 3 steps in the $x$ direction and 5 steps in the $y$ direction. So intuitively, taking a step along some arbitrary direction causes a change along the x-axis as well as along the y-axis. Taking the dot product for the directional derivative sums the changes along the x and y-axis.

So now we have directional derivatives which are essentially a generalization of partial derivatives to deal with any arbitrary direction in our input plane. When training neural networks, the problem we seek to solve is that: given that we are at a point say (2, 3) which corresponds to a loss (the output of our function) of t, we want to know the direction that would result in the greatest increase in our loss? Once we know this direction we take a step in the opposite direction which would lead to the greatest reduction in the loss. Notice that I'm placing an intentional emphasis on the word direction. We are looking for the best direction and lucky enough we already have a tool that gives a measure of how good (or bad) a particular direction is, which as you may have guessed is the directional derivative.

With directional derivatives, one way we could solve this problem is to find the directional derivative of all possible directions in which we could move. The best direction would be the direction with the largest directional derivative. But that would be too slow to compute, think about the number of possible directions in which we could move, the list is endless. However, the idea is good, we just need a simpler way to find the direction with the maximum directional derivative.

Our objective now is to find:

$$\max_{\lvert \vec{w} \rvert =1} \nabla f(a, b) \cdot \vec{w}$$

Notice that the vectors in the equation above have a magnitude or length of 1. In a sense, this ensures that we don't end up picking the wrong vector just because it has a larger magnitude than the rest and hence would maximize the dot product even though it's pointing in the wrong direction.

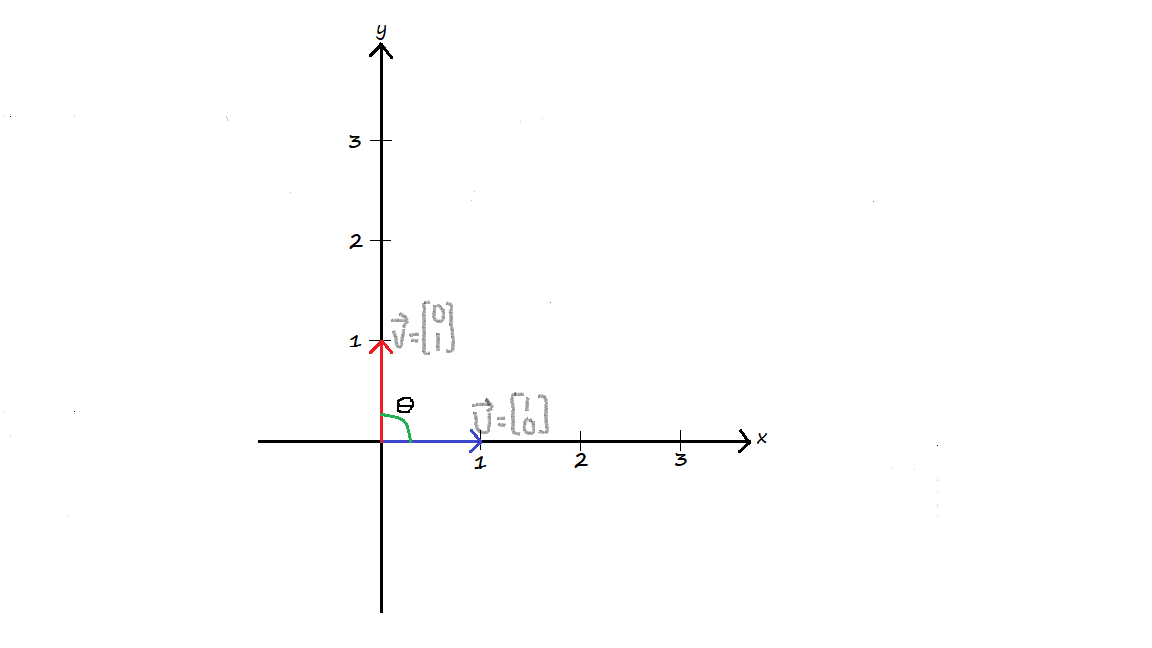

The directional derivative as has already been stated is found by taking the dot product of the gradient and the vector pointing in our desired direction. The dot product possesses a very nice property that would allow us to find the direction that maximizes the directional derivative without having to consider all the possible directions. The dot product measures the similarity between two vectors. It assigns a score to how much the two vectors are traveling in the same direction. Formally, the dot product between two vectors $\vec{u}$ and $\vec{v}$ is: $$\vec{u} \cdot \vec{v} = \lvert \vec{u} \rvert \lvert \vec{v} \rvert cos \theta$$

Where $\theta$ is the angle between the two vectors.

In the illustration above, when $\vec{u}=\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$ and $\vec{v}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$, their dot product is 0 because there is no similarity between them, $\vec{u}$ is pointing purely in the $x$ direction (it has no $y$ component whiles $\vec{v}$ also points solely in the $y$ direction. The angle between them is $90^\circ$ (they are perpendicular) and $cos(90^\circ)=0$. When, $\vec{u}=\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$ and $\vec{v}=\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$, the dot product is maximized because they are pointing in the same direction. The dot product, in this case, is 1 because the angle between them is $0^\circ$. $$\vec{u} \cdot \vec{v} = 1 \cdot 1 \cdot cos(0^\circ) = 1$$

The magnitude of the vectors does not have an impact on the result of the dot product because both vectors have a magnitude of 1. Hence the result of the dot product using the formulation above depends on the angle between the two vectors. From the foregoing, it is not difficult to grasp the fact that we are driving at, which is that, for unit length vectors, the dot product is maximized when the two vectors are parallel, that is they point in the same direction or that the angle between them is $0^\circ$

To remind us of our objective, we want to find the vector that maximizes the directional derivative: $$\max_{\lvert \vec{w} \rvert =1} \nabla f(a, b) \cdot \vec{w}$$

The directional derivative is also a dot product and so it flows naturally from our understanding of dot products that the vector that would maximize the directional derivative and result in the greatest increase in our function is the vector that points in the same direction as the gradient which is the gradient itself. This is why the gradient is the direction of steepest ascent. Gradient descent takes a step in the opposite direction because our objective in training is to minimize, not to maximize the loss function.

Hopefully, you've gained some useful insights from this post to help you solidify your understanding of the foundations of neural networks and other machine learning algorithms. The next blogpost will take a look at the chain rule which is the other major concept behind backpropagation.

Resources

Partial and Directional derivatives: Khan Academy: Multivariable calculus

Dot products: Khan Academy: Linear Algebra

Calculus: 3Blue1Brown